A Brief History of Christmas

And there's a lot of this you WON'T see in a Hallmark movie

Christmas did not begin as Christmas.

That is usually the first surprise. We picture a stable, a star, a baby, a chorus of angels who apparently rehearsed. But the holiday we recognize today is a layered thing, built over centuries — like an old town where every generation just kept adding streets and buildings, eventually making traffic accidents and burglaries inevitable.

Long before anyone talked about December 25, people in the Northern Hemisphere were already paying close attention to this time of year. They had to. Winter could kill you. Food ran low. Darkness lingered. The sun seemed to be losing a fight.

So they marked the turning point.

Around the winter solstice — the longest night of the year — pagan cultures across Europe lit fires, burned logs, decorated with evergreen branches, and held feasts. The hope was simple and practical: the sun is coming back. Life is not done yet. Evergreen plants mattered because they stayed green when everything else died back. They were proof that endurance was possible.

There were gods involved. There were rituals. There was drinking. There was probably singing that sounded better after the drinking.

The Romans held Saturnalia, a raucous, rule-breaking festival honoring Saturn. Slaves got a break. Masters loosened up. Order bent. Gifts were exchanged. For a week, the world flipped itself upside down and then went back to normal — which may be the most honest description of any holiday.

When Christianity began spreading through the Roman world, it did what successful movements often do: it absorbed what was already working.

The Bible, notably, does not give a date for the birth of Jesus. Early Christians did not celebrate it at all. Easter mattered far more. But as Christianity became institutional power — both religious and political — it made sense to plant its flags on existing festivals, especially in an empire with a lot of other gods to quietly retire.

December 25 landed close enough to the solstice celebrations to be useful. The message shifted. The light returning was no longer just the sun. It was salvation. Same darkness. New story.

That worked — mostly.

For centuries, Christmas was a mixed bag. In some places, it was solemn and religious. In others, it was loud, drunken, and chaotic. Medieval Christmas often involved feasting, role reversals, street revelry, and the kind of behavior that made authorities nervous. Think less Silent Night, more public disorder with costumes. The Ghost of Saturnalia Past.

Which brings us to the Puritans.

The Puritans did not dislike Christmas accidentally. They disliked it on purpose, with documentation.

To them, Christmas was not biblical. It was pagan. It encouraged excess, idleness, and joy — three things they viewed with deep suspicion. In seventeenth-century England, and later in colonial New England, Christmas celebrations were attacked as immoral and corrupt.

In Massachusetts, Christmas was banned outright in 1659. Celebrating it could get you fined. Shops stayed open. Work continued. The message was clear: December 25 is just another day, and if you think otherwise, you are part of the problem.

The ban did not last forever, but the attitude lingered. In early America, Christmas was unevenly observed. New England treated it like an annoyance. The South and the Mid-Atlantic were more relaxed. For a long time, it simply was not the central holiday we now assume it has always been.

That change came surprisingly late.

The Christmas we recognize today — domestic, sentimental, centered on family, children, and goodwill — begins to take shape in the mid-nineteenth century. And it starts, improbably enough, in England.

Victorian England, to be specific.

Industrialization had pulled people off farms and into cities. Work was mechanized. Time became measured in shifts and whistles instead of seasons. Childhood, which had once been short and utilitarian, began to be seen as something worth protecting — at least in theory, and not always in practice.

Into this world came a reshaped Christmas.

Prince Albert, husband of Queen Victoria, helped popularize the Christmas tree after German traditions were publicized in England. Illustrated newspapers showed the royal family gathered around a decorated tree. People noticed. People copied.

Christmas cards followed. Advances in printing made them cheap enough to send. They allowed people to say something kind without having to show up in person and say it face-to-face — which remains one of civilization’s great achievements.

Caroling became formalized. Old bawdy folk songs were cleaned up and repurposed. New ones were written. Groups went door to door not to demand food or drink, as they once had, but to offer music in exchange for a warm reception.

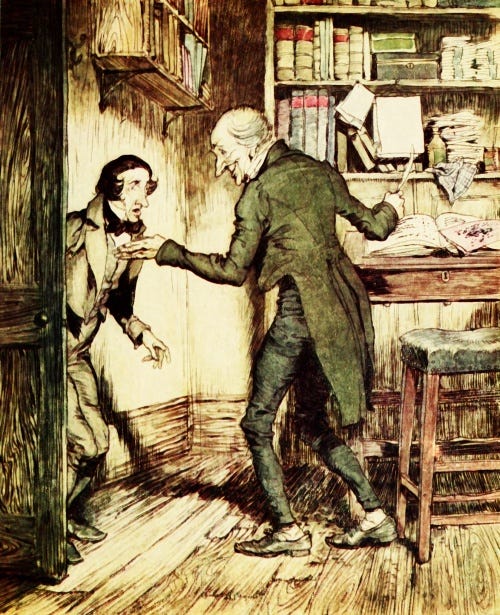

And then there was Charles Dickens.

In 1843, Dickens published A Christmas Carol, which did more to define modern Christmas than any sermon ever delivered. It reframed the holiday as a moral event. Be generous. Notice the poor. Pay attention to one another. Redemption is possible — even late in life, even for people who have made a mess of things.

It landed because the culture was ready for it.

From there, Christmas crossed the Atlantic again, this time transformed. In the United States, the holiday slowly shed its rowdy edges and grew into a quieter, home-centered ritual. Gifts shifted toward children. Churches leaned into the nativity story. Retailers, noticing an opportunity, leaned into everything else.

What’s Christmas now without an ice-cold Coke in Santa’s hand?

By the late nineteenth century, Christmas was no longer suspicious. It was respectable. Eventually, it became unavoidable.

So what we celebrate now is not one thing. It never was.

It is a pagan solstice festival wearing Christian clothing, softened by Victorian sentiment, shaped by literature, reinforced by commerce, and powered by nostalgia. It is about light returning, stories repeated, and people trying — sometimes successfully — to be a little better than they usually are.

Which is not nothing.

Given the darkness of winter, the persistence of history, and the general state of humanity, that might actually be enough.

As for the reason for the season, you can attribute that to axial tilt.

And living in the Northern Hemisphere.

Really enjoyed this! May we all celebrate with our better angels.

Well written and very accurate. So why is it that everyone wants to fight about which greeting/wishes of a happy season is the appropriate one? Because people don't read enough. Or understand enough. Or love each other despite our differences enough.

I wish for you, Rob, some peace, some joy, some great companionship, some love and, of course, lots of comfort food. Merry Christmas!