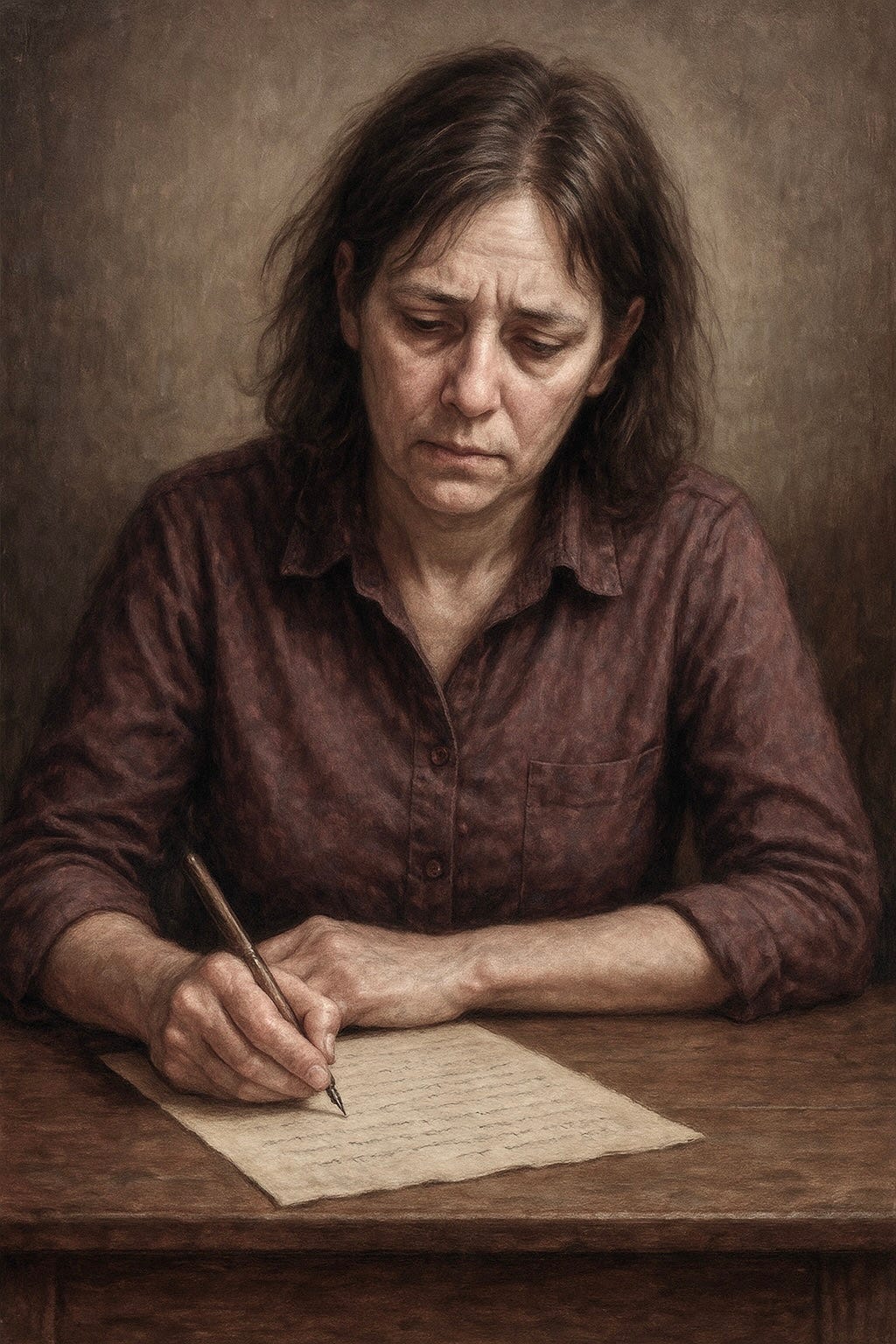

Betty Goes Home

A mother's last letter to her son. A short story

For my son. I don't know if you'll read this. Maybe you'll find it one day. Maybe that's why I can finally tell you all of this.

I used to have talent. That’s what they told me. Said I could draw anything I saw, paint it better than the photograph. I believed them, once. Before the fever hit.

One hundred and four degrees. They packed me in ice at the hosp…