Twenty-Five Years Into the Future We Were Promised

Why we’re still using 19th-century power grids, stuck in low Earth orbit, and what that says about our ambition

Today marks a genuine milestone: we are celebrating the 25th anniversary of the 21st century. Yes, I know what you’re thinking—didn’t we already do this back in 2025? But no. The 21st century actually began on January 1, 2001, not 2000.

This isn’t me being difficult. The CE calendar—or AD, if you prefer—started with Year 1. There was no Year 0. Count from 1 to 100, and you finish the first century at 100, not at 99. The 20th century ended on December 31, 2000. The 21st century began the next morning.

So here we are. A quarter-century into the future.

And I have questions.

The Future That Never Quite Arrived

Science fiction has always been our dreambook. Our blueprint for tomorrow. And looking back at what the 20th century promised us about 2026, well, the results are mixed at best.

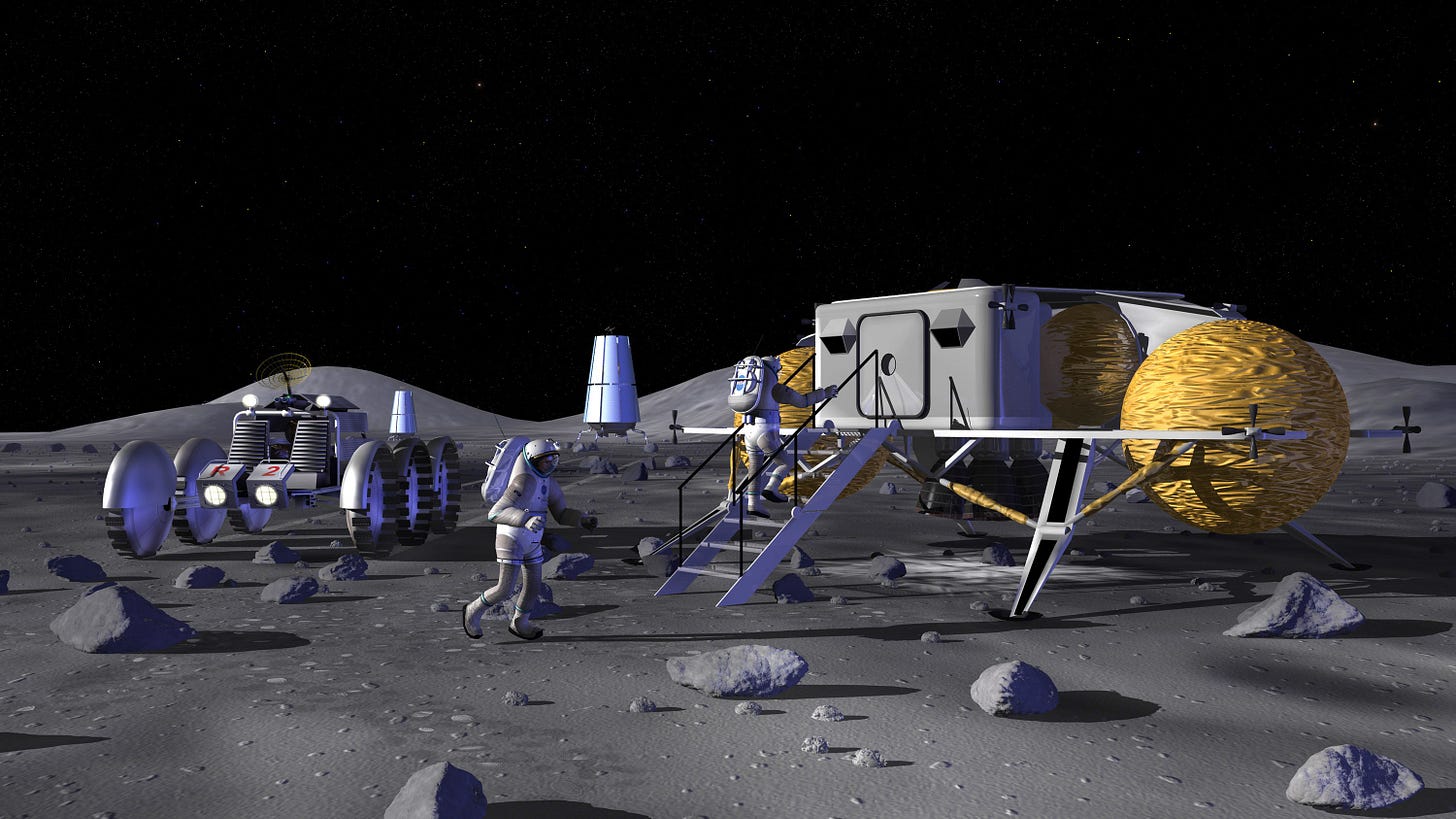

We were supposed to have flying cars. We don’t. We were promised robot butlers to handle the chores. Instead we have Roombas that get stuck under the couch. We were told there would be colonies on Mars and weekend trips to orbital hotels. We have neither, though to be fair, we’re getting closer on that second one.

On the other hand, some things would look like pure sorcery to our ancestors. We carry supercomputers in our pockets. We can video-call anyone, anywhere, for free. AI can generate images and hold conversations and write code. Medicine has made leaps that would have seemed miraculous fifty years ago.

But here’s what gets me: many of our disappointments aren’t about impossibility. They’re about giving up.

Why Am I Still Plugging Things Into the Wall?

Here’s a question that bothers me more than it probably should: why are we still plugging every device in our homes into electrical outlets like it’s 1895?

Wireless power transmission exists. Nikola Tesla was experimenting with it over a century ago. We have wireless charging pads now. Researchers have transmitted real amounts of power across actual distances. We know how to do this. So why isn’t my house powered wirelessly? Why do I still plan my furniture around outlet locations? Why am I still on my hands and knees behind the TV with a flashlight, trying to plug in one more thing?

And speaking of Victorian technology—why do we still have power lines hanging on wooden poles? Every major storm knocks out power to thousands of people because we’ve decided to leave critical infrastructure completely exposed to the weather. We act surprised when this happens. Every single time.

Underground power lines exist. They cost more up front, sure. But they’re more reliable, they need less maintenance, and they don’t turn every street into a tangle of cables and transformers.

We could do better. We’ve simply decided not to. The answer is economics and inertia. We’ve chosen to live with 19th-century solutions because changing them seems like too much trouble.

The Great Space Exploration Stall

And then there’s space.

Arthur C. Clarke imagined missions to Jupiter and Saturn by 2001. The reality? By 2001 we’d just started living continuously on the International Space Station. Now that station is getting ready to retire, and we haven’t been back to the Moon since 1972.

1972.

That’s more than half a century ago.

Did we really get bored with the Moon because we beat the Russians? It seems like maybe we did. The Apollo program was never really about science. It was about winning. Once we planted the flag and declared victory, the public stopped caring and the politicians stopped funding. NASA’s budget went from over four percent of federal spending during Apollo to about four-tenths of one percent today.

We had the capability to keep going. We could have built a Moon base. We could have gone to Mars decades ago. Instead we came home and spent fifty years in low Earth orbit, building and rebuilding space stations, dreaming about what might have been.

SpaceX has shown that reusable rockets can slash launch costs. Multiple countries and companies are planning lunar missions right now. But we’re decades behind where we could have been if we’d just kept going.

We didn’t lack the technology. We lacked the will.

What This Means

Here’s the uncomfortable part. The real problem is almost never that something is impossible. The problem is that we can’t stay focused long enough to finish it. The problem is funding and priorities and whether we can maintain our ambition past the initial excitement.

We could have wireless power in our homes right now. We could have buried power lines. We could have Moon bases. The physics works. The engineering is sound. What we don’t have is the commitment to actually do it.

In a way, this makes it worse. If these things were impossible, we could at least say we tried our best. Instead, we’re just living with the slow grind of bureaucracy and budget cuts. We’re choosing “good enough” over “better” every single time.

The only place where technological progress never seems to stall is warfare and surveillance. That’s where the funding flows — and now, increasingly, where the electricity goes, as AI systems soak up more and more power.

A Quarter-Century In

So here we are. Twenty-five years into the real 21st century. We’ve done remarkable things with computers and communication and medicine. But in fundamental ways—in how we power our homes, in how far we’ve traveled from Earth—we’re still living in the past.

The 21st century is only a quarter done. We still have time to build the future we always imagined.

We have the knowledge. We have the tools.

What we need is the spine to actually use them.

It’s not too late. Not yet.