Making People Disappear

History is not just what happened. It's what keeps trying to happen.

Before the arrests, before the camps, before the smoke—there were signs.

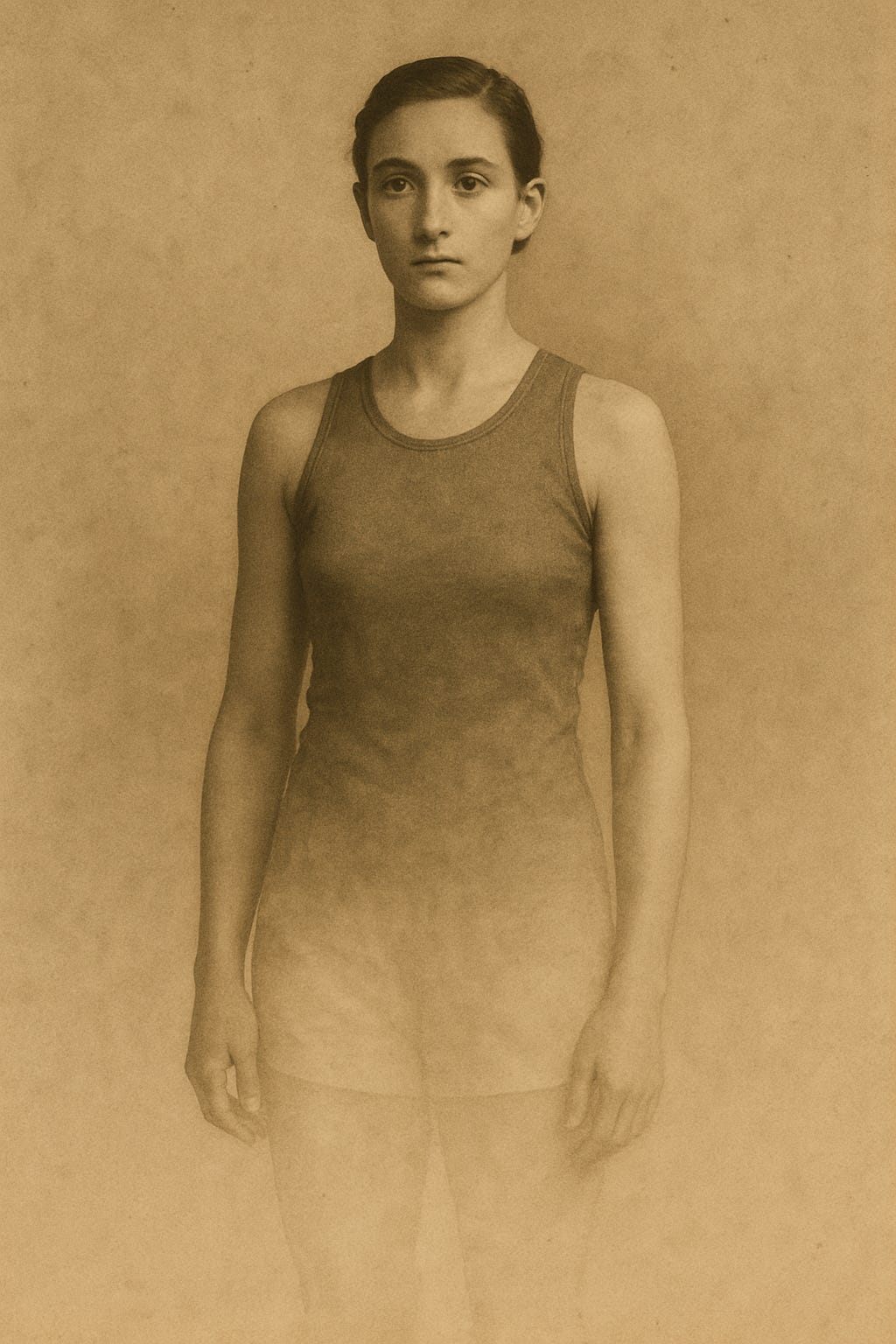

Not warning signs. Literal signs. Names removed. Titles crossed out. Offices reassigned. Teachers dismissed. Doctors erased from hospital directories. Athletes kept from playing sports. Their crime? Being born Jewish.

When we think of the Holocaust, we often skip ahead to the worst c…