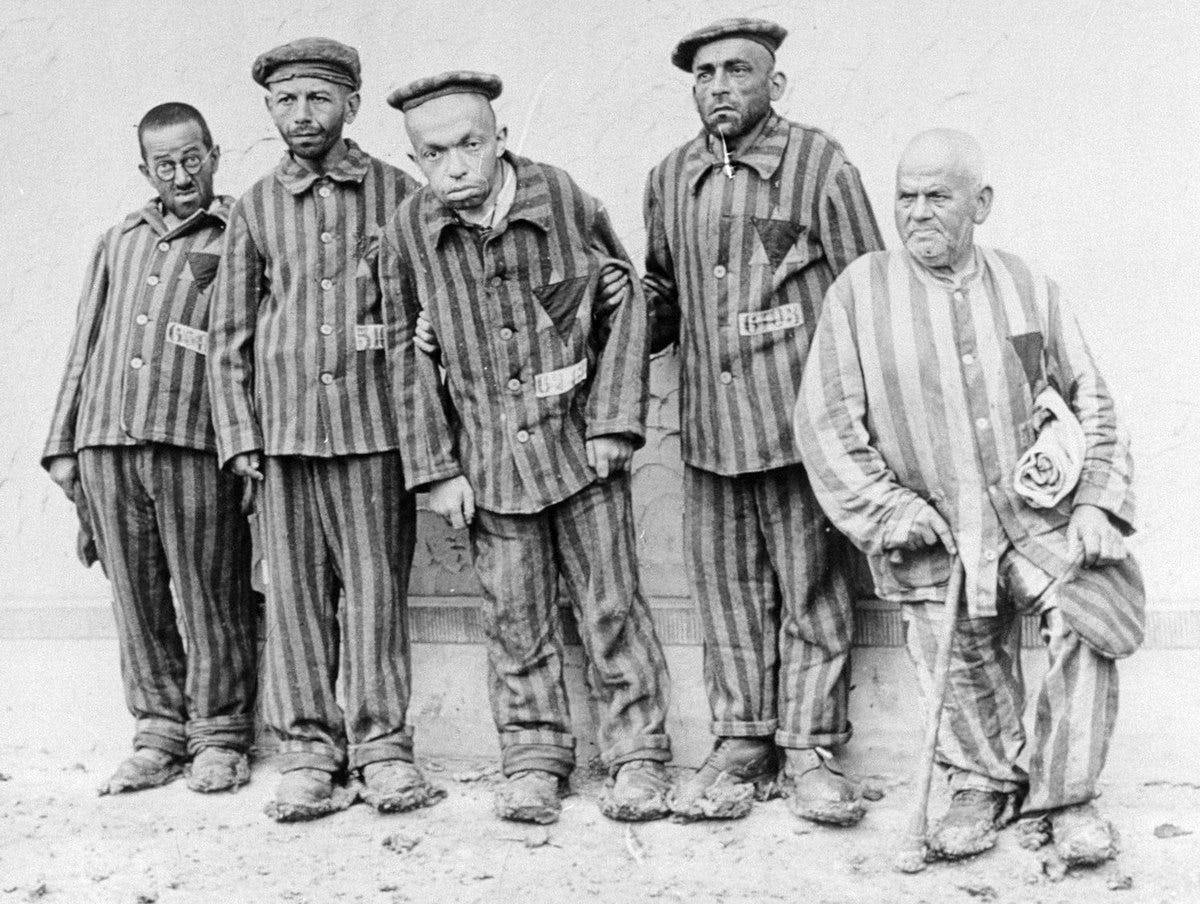

The Useless Eaters: A Warning From the Past

How the Nazis dealt with unemployment, homelessness, and disability—and why we must remember

In the early days of Nazi rule, Germany still bore the scars of the Great Depression. Unemployment was high, morale was low, and fear was easy to weaponize. Hitler didn’t just promise jobs, he promised order. And to restore that order, the Nazis needed someone to blame.

That’s where the so-called “work-shy” came in.

The term sounds almost comical today, l…