Valentine’s Day Wasn’t Invented by Hallmark — Here’s the Real, Surprising History

From medieval poetry to Roman myths, the truth about February 14 is far stranger — and far older — than the greeting card conspiracy.

Every February, right on cue, the same line makes the rounds: Valentine’s Day was invented by greeting card companies to make us feel inadequate and spend money.

The joke was immortalized in the 2004 film Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, when Jim Carrey’s character says that the holiday was created “to make people feel like crap.”

It’s a good line. It’s also wrong.

Valentine’s Day predates Hallmark by centuries. In fact, it predates commercial greeting cards by hundreds of years — and its origins are far stranger, murkier, and more interesting than the cynical version suggests.

It’s a story about Roman rituals, Christian martyrs, medieval poetry, and the slow, unpredictable evolution of culture.

The Roman Festival Theory — Probably a Dead End

One of the most persistent origin stories ties Valentine’s Day to Lupercalia, an ancient Roman fertility festival held in mid-February.

Lupercalia was real. It was loud, chaotic, and involved ritual sacrifice. But according to modern scholarship, it likely had nothing to do with romance.

Krešimir Vuković, author of Wolves of Rome: The Lupercalia from Roman and Comparative Perspectives, has argued that the connection between Lupercalia and Valentine’s Day is essentially a modern invention. The only real overlap? Timing on the calendar.

There is no reliable historical evidence that Lupercalia involved pairing lovers or exchanging romantic notes. The popular image of men drawing women’s names from jars appears to be an 18th- or 19th-century reconstruction — a tidy explanation for a holiday whose actual roots were unclear.

The Martyrs Named Valentine

Another theory centers on early Christian history.

There were at least two third-century martyrs named Valentine who were executed on February 14. Over time, both became associated with sainthood.

The problem? There is no early evidence linking either martyr to romance.

According to Encyclopaedia Britannica, Valentine’s Day did not become associated with romantic love until about the 14th century — about a thousand years after those executions.

That long gap matters. If February 14 had truly been a romantic feast day since late antiquity, we would expect medieval Europe to have left some trace of it. It didn’t.

For centuries, February 14 was just another saint’s day on the Christian calendar.

Enter Chaucer — And the Birds

The first clear connection between February 14 and romance appears in medieval England.

In the late 14th century, Geoffrey Chaucer wrote a poem — often identified as Parlement of Foules — that associated St. Valentine’s feast with the mating season of birds. In his telling, February was when birds chose their partners.

In medieval Europe, the idea that nature itself paired lovers in mid-February captured the aristocracy's imagination. Courtly love culture was already thriving. The symbolism fit.

By the early 1400s, the French Duke of Orléans — imprisoned in the Tower of London — was writing to his wife in February 1415, calling her his “very gentle Valentine.” He described himself as “sick of love.”

By the time William Shakespeare wrote Hamlet around 1600, the concept of a “valentine” was well established. Ophelia refers to herself as Hamlet’s valentine. The cultural association was already embedded.

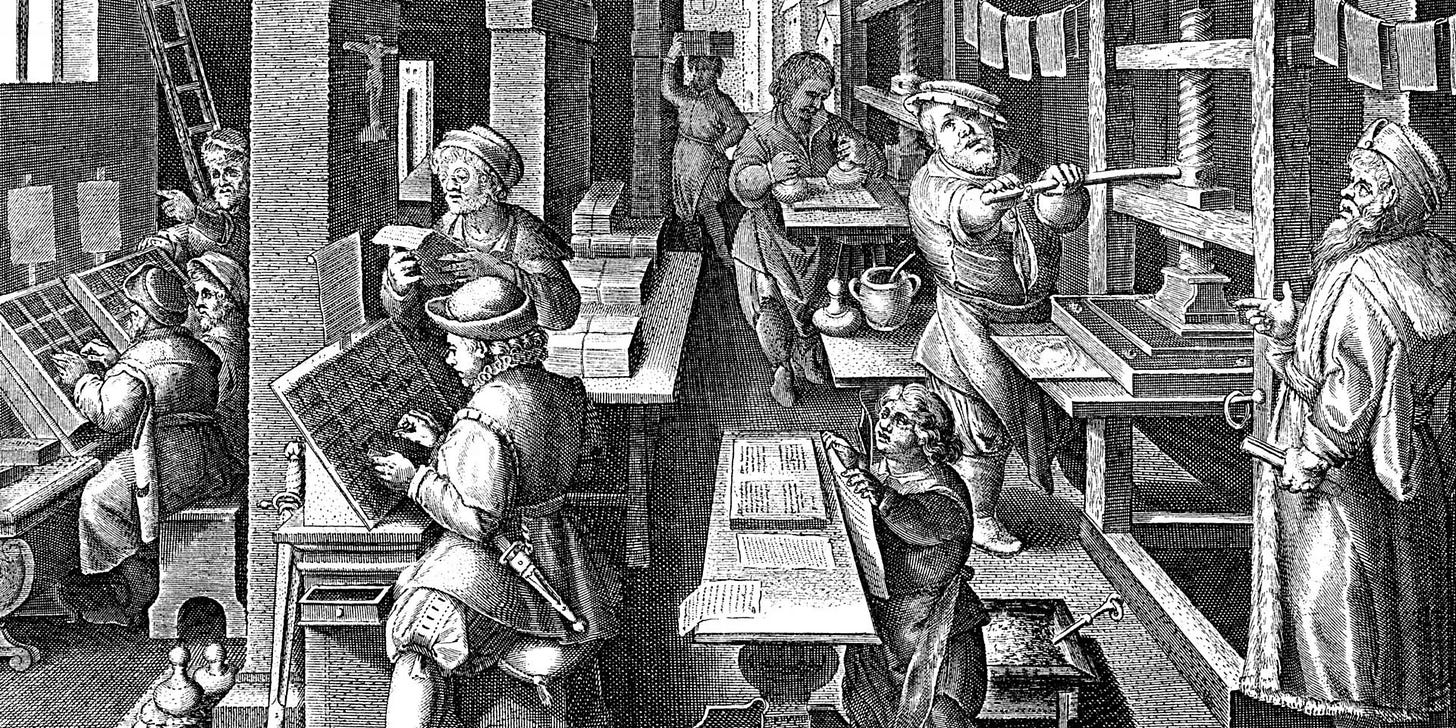

The Printing Press Changes Everything

Fast-forward to the 1500s.

People were already exchanging handwritten valentines.

By the late 1700s, commercially printed cards were circulating in England. The Industrial Revolution made printing cheaper. Paper became more accessible.

The holiday didn’t start with commercialization, but commercialization amplified it.

In the United States, the pivotal figure was Esther Howland, often called the “Mother of the American Valentine.”

In the 1840s, Americans largely imported ornate valentines from England. They were expensive and out of reach for many.

Howland changed that. Around 1849, she began producing valentines using an assembly-line system. Lace, paper, ribbon, printed verses — assembled efficiently and sold domestically.

She didn’t invent the holiday. She democratized it.

Hallmark and the Twentieth Century

By the early 1900s, the holiday was firmly embedded in American culture. In the 1910s, Hallmark began offering Valentine’s Day cards.

Hallmark didn’t create Valentine’s Day. It refined its aesthetic. It standardized the look of romance in ink and cardstock. It expanded distribution. It leaned into sentimentality.

Over the twentieth century, candy companies, florists, jewelers, and restaurants joined in. There was lots of money to be made, and boy, did they make it.

The Real Story Is More Interesting Than the Myth

The “greeting card companies invented Valentine’s Day” narrative is satisfying because it plays into capitalist suspicions: that everything meaningful eventually gets monetized.

And that part is true. But monetization is not the same thing as creation.

Valentine’s Day is older than Hallmark. Older than the United States. Older than the printing press. Possibly older than the Middle Ages — though its romantic meaning probably isn’t.

Its history is messy, fragmented, and incomplete.

Which is exactly what you would expect from a tradition that survived for more than 600 years.

Thank you Rob--and good timing--I was just thinking about refreshing my memory about the history of Valentine's Day ❤️. I always enjoy your writing and I am thankful that you include me for free. Soon I will upgrade as I will have a small income in a few months but in the meantime I appreciate you every day. And today...have a happy Valentine's Day.